Because people "are liable to be imposed upon by charlatans and incompetent physicians and surgeons" and because "it is

of the highest importance that none but persons with competent qualifications should be allowed to practice a profession

to whose skill and ability the life of an individual is entrusted," the General Assembly passed "an act to protect the

citizens of this Commonwealth from empiricism" on February 23, 1874. The act prohibited the practice of medicine to anyone

"who has not graduated at some chartered school of medicine in this or some foreign country." Physicians who had been practicing

"regularly and honorably" for ten years were exempt from this requirement and those practicing for five years were given one

year to comply with its provisions.

The governor was empowered to appoint five-member boards of medical examiners in each of the state's judicial districts to meet

annually "to examine all applicants who desire to practice medicine in any of its departments: chemistry, anatomy, physiology,

obstetrics, surgery, and so much of practical medicine as relates to the nomenclature, history, and symptoms of disease." Persons

found in violation of the act were to be fined fifty dollars for the first offense and one hundred dollars for each subsequent

offense and imprisoned for thirty days.

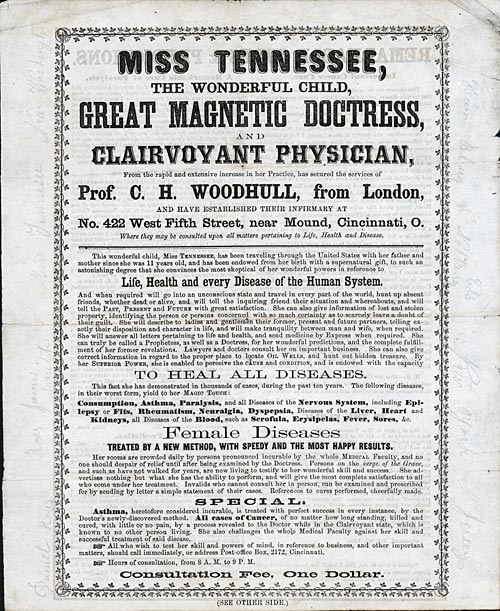

"Miss Tennessee," Tennessee Claflin, billed herself as a "great magnetic doctress" and "clairvoyant physician." She and her sister, Victoria Woodhull, 1872 presidential candidate for the Equal Rights Party, became New York stockbrokers and the editors of Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly, which advocated free love, spiritualism, and Woodhull's political hopes. Claflin was also a favorite of millionaire Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. The broadside, printed in Cincinnati, announced "Prof. C. H. Woodhull, from London" was joining Claflin's Cincinnati practice and infirmary. Canning Woodhull was, in actuality, the American husband of Victoria Woodhull. Kentucky Historical Society Collections.